The case for using avatars in today's digital learning is not hard to make.

We are present at this conference because of the future--the future of digital learning and a desire to explore its possibilities. This presentation argues that the avatar learning agent will emerge as a common fixture in future digital learning environments, whether 3D immersive worlds or the world of Adobe Captivate.

The argument begins with some old news: Higher education has been radically transformed by digital technology and the digital generation. Over a decade ago, The Drucker Foundation (Hesselbein, Goldsmith, & Beckhard, 1997) warned that our traditional teaching methods were outmoded and the physical institutions themselves were "hopelessly unsuited and totally unneeded" (p. 127). The Drucker Foundation arrived at its apocalyptic, pull-the-plug moment by observing the demographic shift in students, a change memorably captured in Marc Prensky's 2005 description of them as "digital natives" and their teachers as "digital immigrants." Prensky's categories imply a third label coveted by few educators: "digital aliens."

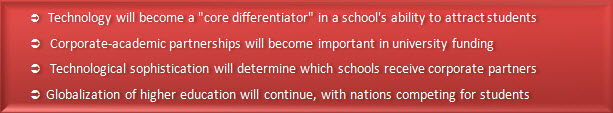

The transformation of how students learn, what we teach, and what it means to be an educated person in the 21st century is a worldwide phenomenon. A global survey (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2008) of corporate leaders and higher education executives in Europe, Asia-Pacific and the U.S. reports that digital learning technology is not only common, but:

Multimedia in the Core

If someone designs a logo for the new digital tool bag, the word "multimedia" should be centered in all caps. Two decades of research have established that students across the board learn more from multimodal, multimedia lessons than from words alone. Since 1989 at least 11 major studies have confirmed this observation (Mayer, 1989; Mayer & Anderson, 1991, 1992; Mayer, Bove, Bryman, Mars & Tapangco, 1996; Mayer & Gallini, 1990; Moreno & Mayer, 1999b, 2002).

In each major study, researchers compared the test performance of students who learned from animation and narration versus narration alone; or from text and illustrations versus text alone. In all 11 studies, students who received a multimedia lesson consisting of words and pictures performed better on subsequent tests than students who received the same information in words alone.

Across the 11 studies, students who learned from words and graphics

produced 55 percent to 121 percent more correct solutions to problems

than those who learned from words alone.

Across the 11 studies, students who learned from words and graphics

produced 55 percent to 121 percent more correct solutions to problems

than those who learned from words alone. Richard Mayer was one of the first to study this remarkable difference in learning and termed it the multimedia effect, part of a set of six design principles formalized by Mayer and colleagues like Ruth Clark in research studies and instructional design manuals that help provide a scientific foundation for multimedia learning throughout corporate training units, colleges and universities.

After two decades of research in this area, the "Multimedia in the Core" program at the University of Southern California should come as no surprise. USC's innovative program is the logical next step: from students learning via multimedia to students demonstrating their learning via multimedia projects that they produce.

USC's Institute for Multimedia Literacy has designed three distinct programs to help achieve its mission of "developing educational programs and conducting research on the changing nature of literacy in a networked culture." First came the Honors in Multimedia Scholarship program in 2003 that culminates in a student producing a multimedia Honors Thesis Project in his or her major. In 2006, a Multimedia in the Core Program was launched to supplement USC's General Education courses with multimedia labs that students use to produce projects that substitute for written papers. In 2007, ILM's Multimedia Across the College Program added upper-division courses to the mix by providing students multimedia instruction in their majors.

Does USC now qualify as a one of the new "digital universities" predicted by The Drucker Foundation and The Economist Intelligence Unit? Is text-based literacy being replaced by multimedia literacy at one of America's best known universities? Would avatars, i.e., learning agents or pedagogical agents, be familiar to these digital native students, who are described by one of their IML teachers as:

" . .

. a new generation. They have skills and abilities far beyond

anything that we have ever seen before." This teacher could have added that, along with their skills and abilities, these students also bring with them a new set of expectations for learning materials, |

The Gold Rush

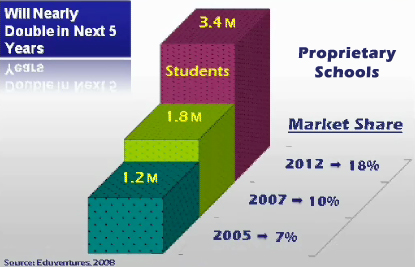

Another argument for avatars comes from what Laws (1996) calls higher education's "gold rush"--the explosion of web-based learning for adults who need and are willing to pay for pajama-clad convenience in order to earn or finish a degree while working and parenting full time.

Some of the most

aggressive

prospectors mining this vein are for-profit education

corporations that have become synonymous and infamous with adult online

learning: Apollo Group and its flagship University of Phoenix, Career

Education Corporation, ITT Technical Training, DeVry, Capella, Jones,

Kaplan, Strayer and more.

Some of the most

aggressive

prospectors mining this vein are for-profit education

corporations that have become synonymous and infamous with adult online

learning: Apollo Group and its flagship University of Phoenix, Career

Education Corporation, ITT Technical Training, DeVry, Capella, Jones,

Kaplan, Strayer and more. Data from groups like the Sloan Consortium and Eduventures are difficult to ignore and make Drucker something of a Delphic oracle to traditional education's confused Oedipus. Sloan-C's latest survey, Staying the Course: Online Education in the United States, 2008, measured a 12 percent growth in online enrollments from the previous year, when the growth rate was 9.7 percent. Figures from both years far exceed the 1.2 percent overall growth of students in higher education and make a persuasive case that significant numbers of students are opting for online education to complement their f2f courses or to replace them altogether.

Whether it's called a gold rush or enrollment bonanza, today there is historic pent-up demand for online education in America. In 2007, only 37 percent of this country's adults had earned an associates degree or higher, compared to 50 percent and more in Canada, Japan, France and Korea (Stokes, 2009). For this nation to stay competitive and for institutions of higher learning to stay in business, both will need to educate more adults in digital classrooms. Especially adults of color.

As Peter Stokes, executive vice president and chief research officer at Eduventures, observes: In 1980, whites accounted for 82 percent of the U.S. population. In 2020, the figure will be 63 percent, with proportional increases in the fastest growing population segments, Hispanics and blacks, both of whom have historically lower achievement in higher education.

In addition, America's new president has promised to retrain millions of workers displaced by the current economic downturn, and has put Federal dollars behind his promise. Higher education received a significant funding boost and loan reform in the Economic Stimulus Bill and 2010 budget ("The Final Stimulus Bill," 2009 & OMB, 2009).

As a dean at our state university put it, "Either we give this new group of college students what they need, or our competition will." Her statement is a call to arms not only for increased availability of online offerings but also for improving their quality. Recently a columnist for U.S. News & World Report (Clark, 2009) wrote: "A survey of professors found that nearly half of those who had taught an online course felt that online students received an inferior education." Then she offers an upside: "Analysts say the market and technological forces that are driving down prices will cause some schools to improve services and quality."

As the literature shows, one way to improve the quality of the online learning experience is with multimedia materials that contain learning agents.

Enter the Avatar

The Personal-Agent Effect: The multimedia effect and USC's innovative programs provide excellent starting points for understanding one of the key aspects of avatars in digital learning: the impact of personalization.

One of the most cited studies in this regard was conducted by Moreno and Mayer (2000), who asked if the use of personalized messages (use of first- and second-person language) would increase learning in multimedia lessons. In two of their experiments, groups of students were presented lessons in a personalized style by avatars ("pedagogic agents"), and other groups were presented lessons in a neutral style: audio and written text in the third person. In both experiments, the lessons containing avatars who spoke in a personalized way produced deeper learning, better problem-solving scores, and retention than did the neutral style.

An additional study (Moreno, Mayer & Lester, 2000) showed similar results. In "Life-Like Pedagogical Agents in Constructivist Multimedia Environments," the researchers sought to understand if science students who learned interactively with a life-like pedagogical agent named Herman would show deeper understanding than students who learned in a conventional environment. Although both groups demonstrated the same levels of factual recall, students taught by a life-like pedagogical agent performed better when asked to apply their knowledge in problem-solving scenarios.

To explain this result, the researchers concluded that lessons with the pedagogical agent generated in students a higher level of interest in the material and higher motivation to learn. The researchers termed this a "personal-agent effect" and attributed it to the well-documented notion that students perceive contact with learning agents also as social interactions (Reeves & Nass, 1996).

|

|

The

Modality Effect: An additional

goal of the

study was to investigate the

impact of learning agents on the "modality effect"--the phenomenon that

students learn better when verbal information accompanying the visual

portion of a lesson is spoken rather than written, resulting in a

reduction of cognitive load on working memory (Lee &

Bowers, 1997; Mayer & Moreno,

1998; Moreno & Mayer, 1999). Once again, students who learned

with the voice of an avatar not only rated the lesson more favorably;

these students also recalled more and were better able to use what they

had

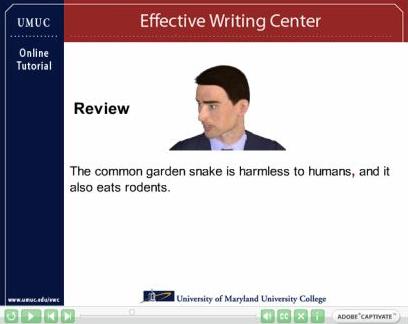

learned to solve problems. The Self-Reference Effect: These results mirror what we at UMUC discovered when we first presented an animated avatar lesson to a class of students. Our "Virtual Tour of the Effective Writing Center" was conducted by Avatar Dave, who used personalized language to present our traditional text materials. |

Psychologists have recognized this phenomenon as a basic principle of human behavior and call it the "self-reference effect." Simply, humans have greater interest in and memory for information that relates to them. A common example of the power of self reference is the "cocktail party effect." You are engaged in conversation in a crowded, noisy place, but if your name is whispered in the distance, you suddenly hear it.

The Marketing Effect: Today it is easy to find examples of the commercial sector leveraging the ability of avatars to engage us socially and to incite the self-reference effect. Indeed, recent research about interactive agents from marketing studies provides additional support for the effectiveness of avatars in computer-mediated learning.

| For example, Wood,

Solomon and Englis (2005) conducted an experiment

with female

shoppers at a fictitious web site selling "personal apparel." One group

of shoppers selected their

own "shopping

assistant" (avatar), a second group was assigned an avatar, and a third

group had no avatar. Shoppers who were

accompanied

by an avatar participated more in the shopping, displayed greater

confidence in their buying decisions, and were overall more

satisfied with the shopping experience. The researchers hypothesized

that the avatars gave shoppers more trust in the site and more

willingness to spend their money. More important for our

purposes, the most successful avatars in this study were the most

realistically human ones. Social Intelligence of Avatars One of the most valuable overviews of avatar use in business and education comes from Byron Reeves (2000) at Stanford University's Center for the Study of Language and Information. Reeves bases his analysis on the significant body of research which shows that when we engage with media, including computer-based media, we process the experience |

Automated

Conversation Agents

All major instant messaging systems, online forum systems, and massive multi-user role-playing games include avatars today (Persson, 2003). And they're talking. The automated conversation agent, also known as a chatbot or chatterbot, uses low AI (artificial intelligence) to engage and sell us. With low AI, avatars use pattern recognition to select a pre-programmed reply to human input. Financial websites use low AI chatbots to gain user trust for transactions and to reduce costs by using an avatar to automate some customer interactions. |

Although we know on a conscious level that avatars are not real, they nonetheless elicit from us an automatic social response. Just as we do with human actors when watching a movie, we invoke a "willing suspension of disbelief" when interacting with an avatar, allowing us to process its speech, facial expressions and body language as if they are real, although we know that the avatar is merely "acting." The mere belief that one is having a social interaction seems to be enough to significantly increase learning and understanding with avatar-based learning materials are used (Okita, Bailenson & Schwartz, 2007).

The more social intelligence that is present--in other words, the more realistic the acting and the production--the more socially satisfying and rewarding the media experience will be (Bailenson, Yee, Merget & Schroeder, 2006). Indeed, the social intelligence of the media can determine the learner's level of attention, engagement, persistence (over time and sessions), and subjective evaluation of the experience (Reeves, 2000).

In short, users perceive avatars as the source of the message they are viewing (Nowak & Rauh, 2005). Thus, the user's perception of the avatar helps determine how the user reacts to the message. To control the message, the multimedia designer must also to some degree control how the avatar is perceived.

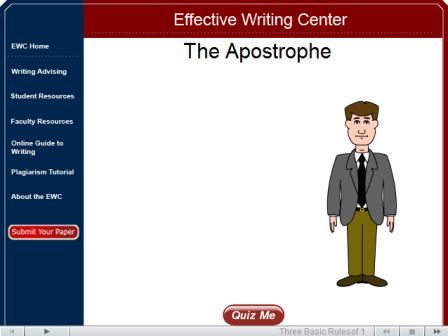

Interactivity: The research of Moreno and Mayer (1999a, 1999b, 2002) suggests that one of the most important ways to increase the quality of social interaction is by increasing the avatar's interactivity, its ability to respond in real time to user feedback. This is one reason why branching scenarios are so important in learning materials. At UMUC's Effective Writing Center, we develop multimedia

|

|

tutorials with animated avatars that respond to a user's input and direct the user to different parts of the lesson based upon on that input. The apostrophe lesson above was done with Media Semantics' Character Builder program, which provides the ability to construct interactive quizzes to accompany the animated avatars. The other example lesson on comma splices and fused sentences was done with Adobe Captivate with an animated avatar created in and imported from Character Builder.

Realism: Not surprisingly, given that a key function of an avatar production is to humanize the online experience, realistic avatars are preferred by most users. One clear demonstration of this preference can be seen on social networking sites when the user is allowed to choose among a photographic avatar, illustrated avatar, or other representation of themselves. On Twitter, for example, users overwhelmingly choose photographic representations of themselves ("Are Avatars Authentic," 2009 & "The Top 7 types of Twitter avatars," 2009).

Yee (2008) reports similar findings about players of online role-playing games. In a survey of over 4,000 players in MMORPGs, Yee found that players generally choose avatars that look like themselves and mirror their stereotypical gender characteristics. In addition, a Zogby survey (Reuters, 2008) of 3585 adults also found that adults in a virtual world overwhelmingly (62%) prefer an avatar that resembles themselves.

Presence & Copresence:These surveys and informal studies confirm what major research projects (Nowak & Rauh, 2005) have found: The more anthropomorphic an avatar appears and acts, the more credible, likable and engaging it will be perceived. One explanation for this effect is the concept of "presence"--the psychological feeling of being there. Researchers studying avatars and virtual environments often refer to the importance of "presence" (the feeling of being there) and "copresence" (the feeling of being there with someone) in the transfer of knowledge and skills in collaborative virtual environments.

Two factors have been identified as primary to creating a sense of presence. First, one consensus that emerges from a review of the literature of presence is: the more multimodal a virtual environment is, the stronger the sense of presence it will generate for users (Romano & Brna, 2001; Sanchez-Vives & Slater, 2005). A pair of Israeli researchers studied one possible explanation: cognitive processing speed. In their study "Multimodal Virtual Environments: Response Times, Attention, and Presence," test subjects in multimodal virtual environments were measured to process sensory input faster, giving them a richer experience in a shorter period of time, and thus heightening their sense of presence (Hecht & Gad-Halevy, 2006).

But avatars also have been shown to play an instrumental role in giving the user a sense of presence in a virtual environment. Numerous studies (Bailenson, Swinth, Hoyt, Persky, Dimov & Blascovich, 2005; Bailenson, Yee, Merget & Schoreder, 2006; Yee, Bailenson, & Rickertsen, 2007; Bailenson & Yee, 2006; Casanueva & Blake, 2001) illustrate the different ways that realistic, social intelligent avatars generate a psychologically heightened sense of presence for the user in virtual learning environments. The heightened sense of presence has also been documented physiologically in one study that measured significant changes in heart rate and galvanic skin responses of test subjects to the presence of avatars, when avatars spoke and when they acted (Slater, et al., 2006). There can be little doubt that virtual environments and the avatars that inhabit them are real for users in very significant ways.

As humans, our brains are wired to connect us to other humans. Social cognition theory argues that this wiring is the product of evolution and is critical to our survival: Our minds analyze the environment and determine an entity's level of anthropomorphism in order to differentiate among inanimate objects, animals, and humans, including an assessment of threat or cooperation (Kunda, 1999). Not surprisingly, research indicates that the more anthropomorphic an avatar is, the more the user will trust it and engage with it (Koda, 1996; Wexelblat, 1997).

In Second Life, the attempt to make avatars more realistic in their appearance and interactions is an intense focus for those working to create body markup languages, improve natural language recognition, design independent virtual agents and more (e.g., EMBOTS). These people are attempting to program the world that Neal Stephenson imagined had been programmed in Snow Crash, a virtual reality in which avatars are indistinguishable from their human counterparts.

|

Based upon this evidence of the ability of

socially

intelligent

avatars to increase student

learning in digital lessons, I set out to

create a digitized version of myself that could be used in the Second

Life tutorials I was creating and, if it succeeded, to use the

avatar in other

materials for students. My

working definition of "human

avatar" became a non-interactive video character composited into any

virtual world, web page, or multimedia lesson presented to

students. Merry Prankster:The project began as a joke. After buying a HD camcorder, I was looking for ways to make money with it to offset the extravagant price. I knew of stock photo sites that bought freelancer work. What about stock video sites? In my search I downloaded one site's free sample (Stock Footage for Free) of a gorgeous beach bathed by the tropical Caribbean. Since I was also about to post a weekly video lecture for an online class, and it was the dead of winter, what fun it would be to give my standard |

As you can see from the video above, I downloaded a trial version of software that offered a chroma keying function, hung up a green bedsheet on a broomstick stretched across two step ladders in my front yard, and persuaded my embarrassed wife to operate the camera. Thankfully, I have good-humored students and an understanding wife. But what dawned on me, in what must set some record for slow-wittedness, was that with chroma keying (which has only been around since the 1970s) I could give a video lecture anywhere I had a digital background of.

First Try, Second Life: At the time I was also making orientation videos for students who use my two properties in Second Life, Escribir Park and Escribir House, to fulfill class requirements, so I decided to try a chroma-keyed video in SL. This was another bedsheet production, resulting in a head-and-shoulders shot that was keenly disappointing. It looked no different than a regular PIP and added little that wasn't in the other Second Life tutorials I had been doing, which were screen recordings with voice over and sound effects (see below). The virtual 3D world of Second Life demanded more.

Full-Frontal Avatar: What was missing, of course, was a full-figured avatar that could be composited into Second Life, scaled to size, and animated to interact with the environment and other avatars. Achieving those goals would require a real greenscreen and something more than trial compositing software. I settled on CompositeLab Pro due to price ($149 compared to Adobe Premiere at $350 educational price) and ease of use. I also lucked into a 5' x 7' flexible greenscreen backdrop for $30 (normally $99) as part of one site's holiday specials. Another investment was a Nady wireless microphone for the camcorder ($75). Total investment for this part of the project was around $250, but the result was encouraging--a small, life-like figure that could be easily inserted onto any digital background (see video below). Now, all I had to do was build a greenscreen studio for him to walk around in.

|

|

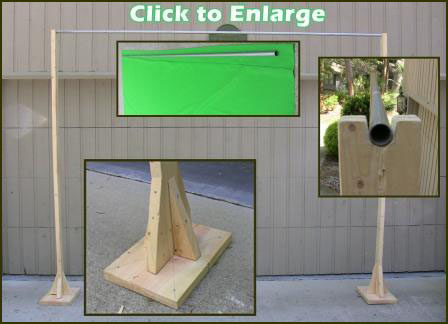

decided to build a

rudimentary stand to hang one piece of greenscreen cloth and lay

another section on the ground. The stand is constructed of 2x4's nailed upright to a 4x12" base

and supported with wedges that I screwed and

nailed into the base (click to enlarge image).

decided to build a

rudimentary stand to hang one piece of greenscreen cloth and lay

another section on the ground. The stand is constructed of 2x4's nailed upright to a 4x12" base

and supported with wedges that I screwed and

nailed into the base (click to enlarge image). At the top of each stud, I rounded out a notch to hold a crossbar from which the greenscreen cloth would hang. An open seam across the top of the cloth forms a hanger pocket that easily accommodated a half-inch wide piece of electrical conduit pipe, which comes in 10-foot lengths. I chose electrical conduit piping for its rigidity (PVC pipe may have sagged), price, and galvanized finish. After the 11-foot panel of cloth was hung, I added one more section of cloth on the ground to provide room for walking forward and back. Unfortunately, as you can see from the video below, this greenscreen stage was not wide enough to provide for adequate lateral movement. In the video, you can see the

|

unnatural movement when the avatar walks in a lateral direction. The avatar's body seems to slide instead of walk. This effect is produced by a lack of digital information during tweening, when the computer adds intermediate frames between stop points (keyframes) to make movement appear natural. The video I supplied to the software simply did not contain enough movement in its frames to be rendered natural looking. Lesson learned.

DIY Greenscreen Studio II: I bought two more sections of greenscreen cloth in order to double the width of the stage to 20 feet. A third section of cloth was purchased to drape over furniture on the stage so the avatar could sit or interact

with

it or other objects

that would appear in the Second Life digital background video. I built

two more

stands using the same materials described above (click to enlarge

image).

with

it or other objects

that would appear in the Second Life digital background video. I built

two more

stands using the same materials described above (click to enlarge

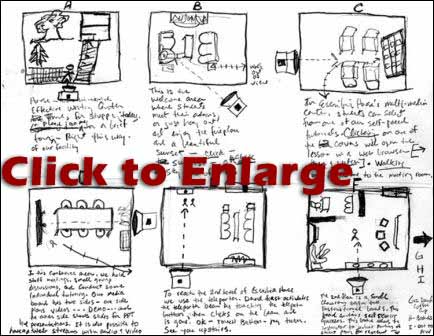

image). For this test I planned a series of seven scenes to take place in and around Escribir House, UM

UC's in-world writing

center. Because Escribir House has five rooms and a number of features

to be shown

in the video, it became necessary to storyboard the video: to draw a

series of rough illustrations for each scene.

Storyboarding allows

pre-planning for camera angles, avatar movements, camera movements, and

timing. Since two video clips from two different worlds--Second Life

and the greenscreen stage--were to be meshed into the illusion

of a single world, storyboarding became essential, as did rewriting the

script to fit the flow and timing of action.

UC's in-world writing

center. Because Escribir House has five rooms and a number of features

to be shown

in the video, it became necessary to storyboard the video: to draw a

series of rough illustrations for each scene.

Storyboarding allows

pre-planning for camera angles, avatar movements, camera movements, and

timing. Since two video clips from two different worlds--Second Life

and the greenscreen stage--were to be meshed into the illusion

of a single world, storyboarding became essential, as did rewriting the

script to fit the flow and timing of action.Digital Video Workflow: Because this video would consist of multiple scenes each composed of two separate videos (a chroma-key segment composited onto a Second Life screen recording), it also became necessary to follow a detailed workflow. A digital workflow is a step-by-step plan for creating a specific digital product. The plan includes all software used and its settings, what to do in each step, intermediate products, even tips. The term originated in photography but today also refers to the creative process used in any digital medium.

| Workflow |

| 1. Shoot greenscreen segment with Canon Vixia HF100 camcorder in AVCHD (Advanced Video Codec High Definition) |

| TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress 2. Launch TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress. Click "Start a new project." Click "Add file" to import .MTS file (MPEG Transport System) of greenscreen clip from camera flash memory. Clip settings in TMPGEnc should be: Display mode: Interlace

3. Click Cut-Edit tab at

top of window. Use Cut-Edit to trim frames of greenscreen video clip

not to be viewed. Click OK.Field order: Top field first Aspect ratio: Aspect ratio: Display 16:9 Framerate: 29.97 4. Click Filter tab at top of window: Use Picture Crop to eliminate areas outside greenscreen on all four sides. 5. Apply other filters as needed (color correction, noise reduction, etc.). Click OK. 6. Click Format tab at top of window. 7. Select QuickTime (.MOV) file output from list of templates on left. Click Select. 8. Under Video Codec, click on "Settings . . . " 9. Under Compression Type, choose Photo JPEG from drop down menu 10. Move slider to "Best." Click OK. 11. Click Encode tab at top of window. 12. Click "Display output preview" icon (magnifying glass) to check for "clean green" on all sides. No black can be visible on any side. If any black is visible, return to Format menu and adjust video dimensions. 13. Click "Encode" to render greenscreen video clip as a .MOV file |

| Fraps

& Second Life 14. Open Second Life and size SL viewer to 960 x 720 with Camtasia Studio 6 screen recording tool or Sizer tool 15. Open Fraps. Click on Movies tab. Click radio button under list of fps. Type into field: 29.97 16. Open greenscreen video clip. Minimize QT player so that it is not obscuring SL viewer. 17. Start Fraps recording in SL. 18. Start greenscreen video clip in QT. 19. Record in SL following verbal and visual cues from greenscreen video clip being played in QT. |

| TMPGEnc 4.0 Xpress 20. Import Fraps SL recording (.avi). Clip settings: Display Mode: Progressive

21. Click OKAspect Ratio" Pixel 1:1 (Square pixel) 22. Click Format tab at top of window 23. Click "Settings . . . " under Video Codec 24. For Compression Type, select Photo JPEG from drop down menu. 25. Position slider to "Best" 26. Click OK 27. Click Encode tab at top of next window. 28. Click "Display output preview" icon (magnifying glass) to check for "clean green" on all sides. No black can be visible on any side. If any black is visible, return to Format menu and adjust video dimensions 29. Click Encode to render SL screen recording as QuickTime (.MOV) |

| FXhome

CompositeLab Pro 30. Launch program and click "Select Video Clip" on startup screen 31. Import SL screen recording .MOV 32. Go to Toolbox > Media Tab > Click folder icon to "Import Media" 33. Import greenscreen video clip 34. Go to Toolbox > Media Tab > Left click on greenscreen video clip thumbnail 35. Drag greenscreen video clip thumbnail to canvas on top of SL recording 36. Go to Timeline > right click on title of greenscreen video clip 37. Select "Apply preset" from drop-down menu 38. Select "Greenscreen key" from list of presets. Click "Apply" 39. Go to Timeline > click on options arrow to expand options for greenscreen clip. 40. Select "Grade" option 41. Go to Toolbox > Info tab 42. Apply Grade options as needed (Saturation, Contrast, Sharpen, Levels, etc.) to greenscreen clip 43. Go to Timeline > click on options arrow to expand options for greenscreen clip 44. Select "Animation" option 45. Use Quad, Scale and Rotation tools to position figure 46. Click "Play" arrow 47. Trim SL screen recording for timing with greenscreen clip 48. Set In/Out frames 49. Go to main menu at top. Click on "Render" tab. Pull down to "Render" option 50. Name file and and select destination. Click Save 51. For Compression Settings, select Photo JPEG from drop down menu. Click OK to render composite project as .MOV |

| Camtasia

Studio 6.1 52. Launch program. Import composite project (size 640 x 480 Custom) and place on Timeline with other clips, if any 53. Edit final video using 640 x 480 dimensions 54. Select "Produce video as . . ." from Produce pod 55. From drop down menu, select "Custom production settings." Click Next 56. Click radio button for .MOV - QuickTime Movie. Click Next 57. Select QuickTime Options tab at top of next window 58. Under Video, click on Settings tab 59. For Compression Type, select H.264 from drop down menu 60. Position slider at "Best" quality setting 61. Click OK 62. Click on "Size" tab 63. For Dimensions, select 640 X 480. Click OK 64. Click Next four times. 65. Name file and choose destination. Click Finish to render video |

Conclusion: Future of the Human Avatar

Although promising work is being done in the field of artificial intelligence to make avatars more responsive to users and easier to program, the beneficial applications of this work for educators seem a number of years away. In the interim, digital compositing provides a quick, easy, cost-effective way to generate a human avatar that fits many of the characteristics of the intelligent avatar of the future.

Digital compositing can bring an online teacher to life in the digital world, a place where students are often expected to learn on their own from programmed materials. The avatar teacher can add the personal dimension of teaching style to the social

| interaction of computer-mediated

learning. The avatar teacher

can perform more movements, provide more expression, and present a more

realistic appearance than current avatars and do not require

programming. As this video shows, I have begun recording video lectures for online classes using a greenscreen in the same manner that the local weather is often produced. Off to the side sitting on a kitchen stool was a laptop displaying a PowerPoint of the presentation that I controlled remotely. The student response to these "productions" is almost always the same: "It was just like being in class." And "All teachers should be required to do this." These comments affirm that the students' interactions with these computer-mediated materials are important social interactions and, furthermore, that the effectiveness of the interaction is largely |

The more life-like the learning agent is, the greater the student interest, perseverance, comprehension and retention.

In Second Life, machinima done with these digitally composited avatars can play an important role in acclimating new users to the basic components of 3D virtual reality education, introducing students to a university's property and offerings in Second Life, and helping students get started with specific projects or lessons. Indeed, members of one class at UMUC who are given the option of presenting a PowerPoint in Second Life have been able to use only these machinima, without any other instruction and without ever having visited Second Life before, to successfully present their shows.

There are multiple possible reasons for the success of this in-world human agent. One is the role of situational context. Research in collaborative virtual environments has shown how users learn from observing the behaviors of others in the virtual world (Blascovich, 2002) just as they do in reality. This digitized human avatar is capable of modeling behaviors to a much higher degree than the animated avatars currently available in Second Life.

Another reason may have to do with the increased expectation for behavioral realism that comes with an increase in realistic appearance. An avatar that appears highly realistic will be perceived negatively unless it behaves as real as it looks (Slater et al., 2001; Tromp, 1998). Although avatars in Second Life can achieve a strong degree of realism in their appearance, the scripting for their actions remains rudimentary and not widely used.

Finally, research has demonstrated that avatars which demonstrate emotional awareness, which is perceived as a significant form of social intelligence, decreases the user's personal distance and increases empathy (Selvarajah & Richards, 2005). The digital human avatar can be as expressive as a real person and thus has the ability to gain more intimacy and credibility with the user.

Its name is self defining. A photofit avatar is produced from a photograph of a person. Justifications for its use are the same as for the human avatar--personalization, realism, and social intelligence that increase the learner's attention and comprehension. Its acceptance is widespread: Google "photofit avatar" a

nd

you will quickly discover literally dozens of freeware and premium

versions of

this software, from one of the most widely used commercial products like Singular

Inversion's FaceGen, popular

with professional animators, to just-for-fun products. Some

free products also allow you to import your photofit avatar into 3D

immersive worlds via realXtend and other products.

nd

you will quickly discover literally dozens of freeware and premium

versions of

this software, from one of the most widely used commercial products like Singular

Inversion's FaceGen, popular

with professional animators, to just-for-fun products. Some

free products also allow you to import your photofit avatar into 3D

immersive worlds via realXtend and other products. Although they are ubitquitious, the only photofit avatar program I've found geared for educators and practical uses in business has been Character Builder from Media Semantics. At $299, Character Builder is an affordable way for nonanimators to add avatars to a variety of learning materials: Captivate, Articulate, PowerPoint, Macromedia Flash (SWF format), and video files that can be used in a variety of ways. Another advantage is that Character Builder doesn't need any other software to produce interactive learning materials that are SCORM compliant. Its Flash and video output can also be used as stand-alone lessons. Finally, the lip-synced, animated avatars starring in your productions are also royalty free, a fact your legal department may want you to document.

Although Character Builder comes standard with some realistic and cartoon avatars to get you started, because the PhotoFit program is also standard, the actual number of unique avatars you can create is infinite. The program offers more than 130 controls to change facial features of any given photo, and the program can also generate random faces on its own, each of which can be altered with the controls. Below is a video which demonstrates the use of Character Builder and PhotoFit to create a recent project for one of UMUC's advisers in the Effective Writing Center.

| Character Builder's PhotoFit Function: Workflow Demonstration | |

welcome messages in advice templates--last fall and spring 28 advisers sent out 6,000 advice templates to students. each one was required to have a personalized multimedia welcome message.

personalization with bios in web tycho and

presence in otherwise boring lectures

Uses: Diversity

The University of Maryland University College is located in the Metro Washington, D.C. area, one of the most culturally diverse areas in the United States. Our school's population of xxxxxx reflects this diversity, . However, the selection of avatars from Media Semantics and other off-the-shelf programs do no.

Photofit animated avatars allow educators to utilize the well-established human disposition to prefer faces of those who look like us (Baileson, Garland, Iyengar & Yee, 2006). We also use physical similarity, including dress, to judge whether another person may share our core values and interests (Zajonc, Adelmann, Murphy & Niendenthal, 1987).

Conclusion

Research indicates that avatars will play an important role in the development of more effective digital learning materials which can, in turn, improve the quality of online instruction at a time when there is economic and social pressure to do so. Avatars help to personalize the online learning experience and to increase a student's interest, attention and motivation to learn. Avatars can achieve these benefits especially well when they display social intelligence, appear anthropomorphic and offer interaction.

At Washington State University's recent Virtual Journalism Summit, Second Life founder Philip Rosedale said that having an avatar will soon be like having an email addresses was in 1989. Back then, whether you liked it or not, Rosedale said, "you had to get an email or the world would leave you behind. Soon all of you will have to get an avatar" (draxtordespres, 2009).

Maybe that applies to avatars in our future digital learning materials as well.

References

Bailenson, J., Swinth, K., Hoyt, C., Persky, S., Dimov, A., Blascovich, J. (2005). The independent and interactive effects of embodied-agent appearance and behavior on self-report, cognitive, and behavioral markers of copresence in immersive virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 14(4), 379-393. Retrieved June 1, 2009 from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/105474605774785235

Bailenson, J., Garland, P., Iyengar, S., & Yee, N. (2006). Transformed facial similarity as a political cue: A preliminary investigation. Political Psychology, 27, 373-386. Retrieved June 11, 2009 from http://pcl.stanford.edu/common/docs/research/bailenson/2005/similaritycue.pdf

Bailenson, J., Yee, N. (2006). A longitudinal study of task performance, head movements, subjective report, simulator sickness, and transformed social interaction in collaborative virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 19(1), 699-716. Retrieved June 10, 2009 from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/pres.15.6.699?journalCode=pres

Bailenson, J. Yee, N., Blascovich, J. & Guadagno, R. ( 2008). Transformed social interaction in mediated interpersonal communication. In Konijn, E., Tanis, M., Utz, S. & Linden, A. (Eds.), Mediated Interpersonal Communication (pp. 77-99). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved June 3, 2009 from http://vhil.stanford.edu/pubs/2008/bailenson-TSI-mediated.pdf

Bailenson, J., Yee, N., Merget, D. & Schroeder, R. (2006). The effect of behavioral realism and form realism on real-time avatar faces on verbal disclosure, nonverbal disclosure, emotion recognition, and copresence in dyadic interaction. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15(4), 359-372. Retrieved May 2, 2009 from ProQuest Education Journals database.

Blascovich, J. (2002). Social influence within immersive virtual environments. In R. Schroeder (ed.), The Social Life of Avatars. London: Springer-Verlag, pp. 127–145. Retrieved June 5, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Casanueva, J. & Blake, E. (2001). The effects of avatars on co-presence in a collaborative virtual environment. Technical Report CS01-02-00, Department of Computer Science, University of Cape Town, South Africa, 2001. Retrieved June 5, 2009 from http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/cache/papers/cs/

26789/http:zSzzSzwww.cs.uct.ac.zazSzResearchzSzCVCzSzPublicationszSzsaicsit01_1casanueva.pdf/casanueva01effects.pdf

Clark, K. (2009, April 2). Online education offers access and affordability . U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved May 1, 2009 from http://www.usnews.com/articles/education/online-education/2009/04/02/online-education-offers-access-and-affordability.html?PageNr=1

draxtordespres. (2009, May 1). Ethnography in Second Life: Resistance is futile! [Video file]. Video posted to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0wEWgTyHXA

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2008). The future of higher education: How technology will shape learning. Sponsored by The New Media Consortium. Retrieved April 12, 2009, from http://www.nmc.org/pdf/Future-of-Higher-Ed-(NMC).pdf

Fletcher, J.D., & Tobias, S. (2005). The multimedia principle. In R.E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 117-134). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Foreman, Joel. Avatar pedagogy. The Technology Source Archives at the University of North Carolina. Retrieved February 7, 2009 from http://technologysource.org/article/avatar_pedagogy/

Hecht, D. & Gad-Halevy. (2006). Multimodeal virtual environments: Response times, attention, and presence. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15(5), 515-523. Retrieved June 9, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database.

Hesselbein, F., Goldsmith, M. & Beckhard, R. (1997). The organization of the future. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, L., Smith, R., Smythe, J. & Varon, R. (2009). Challenge-Based learning: An approach for our time. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Lee, A.Y. & Bowers, A. N. (1997). The effect of multimedia components on learning. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 340-344. Reprint.

Karp, D. (2009). "Are avatars authentic or effective?" Retrieved April 30, 2009 from http://www.limeduck.com/2009/03/04/are-avatars-authentic-or-effective/

Kluge, S. & Riley, L. (2008). Teaching in virtual worlds: Opportunities and challenges. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 5, 127-135. Retrieved February 23, 2009 from http://proceedings.informingscience.org/InSITE2008/IISITv5p127-135Kluge459.pdf

Koda, T. (1996). Agents with faces: The effects of personification. Proceedings of HCI 1996. London.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Laws, B. (1996). Distance learning's explosion on the internet. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 7(2), 48-64. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EJ523018) Retrieved May April 4, 2009, from ERIC database.

Mayer, R. (1989). Systematic thinking fostered by illustrations in scientific text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 240-246.

Mayer, R. & Anderson R. (1991). Animations need narrations. An experimental test of dual-processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Mayer, R. & Anderson R. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 444-452.

Mayer, R., Bove, W., Bryman, A., Mars, R., & Tapangco, L. (1996). When less is more: Meaningful learning from visual and verbal summaries of science textbook lessons. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. & Gallini, J. (1990). When is an illustration worth ten thousand words? Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. & Moreno, R. (1998). The split-attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (1999a). Multimedia-supported metaphors for meaning making in mathematics. Cognition and Instruction, 17, 215-248.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (1999b). Cognitive principles in multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity effects. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 1-11.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (2002). Engaging students in active learning: The case for personalized multimedia messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 724-733.

Nagao, K. & Takeuchi, A. (1994). Social interaction: Multimodal conversation with social agents. Proceedings of the Eleventh National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.aaai.org/Library/AAAI/aaai94contents.php

Nowak, K. & Rauh, C. (2005). The influence of the avatar on online perceptions of anthropomorphism, androgyny, credibility, homophily, and attraction. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1). Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/nowak.html

Office of Management and Budget. (2009). President Obama's fiscal 2010 budget. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/fy2010_key_college/

Okita, S., Bailenson, J., Schwartz, D. L. (2007). The mere belief of social interaction improves learning. In Proceedings of the Twenty-ninth Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. August, Nashville, USA. Retrieved June 11, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Prensky, M. (2005). Listen to the natives. Educational Leadership, 63(4), 8-13. Retrieved April 12, 2009 from http://www.ascd.org/authors/ed_lead/el200512_prensky.html

Reeves, B. (2000). The benefits of interactive online characters. Retrieved April 18, 2009 from http://www.sitepal.com/pdf/casestudy/Stanford_University_avatar_case_study.pdf

Reeves, B. & Nass, C. (1996). The media equation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Reuters, E. (2008). Poll: Most adults don't want fantasy avatars. Second Life News Center. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://secondlife.reuters.com/stories/2008/01/31/poll-most-adults-dont-want-fantasy-avatars/

Romano, D. & Brna, P. (2001). Presence and reflection in training: Support for learning to improve quality decision-making skills under time limitations. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 4(2), 265-278. Retrieved May 11, 2009 from Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection database.

Sanchez-Vives, M. & Slater, M. (2005). From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 6, 332–339. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from Academic Search Premier database.

Selvarajah, K. & Richards, D. (2005). The use of emotions to create believable agents in a virtual environment. International Conference on Autonomous Agents: Proceedings of the fourth international joint conference on Autonomous agents and multiagent systems, July 25-29, 2005. Utrech University, The Netherlands. Retrieved, May 12, 2009 from The ACM Digital Library database.

Slater, M., Guger, C., Edlinger, G., Leeb, R., Pfurtscheller, G., Antley, A., et al. (2006, October). Analysis of physiological responses to a social situation in an immersive virtual environment. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 15(5), 553-569. Retrieved June 13, 2009, from Computers & Applied Sciences Complete database.

Slater, M. & Steed, A. (2001). Meeting people virtually: Experiments in virtual environments. In R. Schroeder, Ed., The Social Life of Avatars: Presence and Interaction in Shared Virtual Environments, Springer Verlag, Berlin, 2001.

Sloan-C. (2008). Staying the course: Online education in the United States, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/survey/staying_course

Stoilescu, D. (2008). Modalities of using learning objects for intelligent agents in learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects. Retrieved May 1, 2009 from http://ijklo.org/Volume4/IJELLOv4p049-064Stoilescu394.pdf

Stokes, P. (2009). From survival to sustainability. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved May 1, 2009, from http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/04/17/stokes

The final stimulus bill (2009). Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/02/13/stimulus

The New Media Consortium. (2005). A global imperative: The report of the 21st Century literacy summit. Retrieved February 8, 2007, from http://www.adobe.com/education/solutions/pdfs/globalimperative.pdf

The top 7 types of Twitter avatars. (2009). 10,000 Words. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from http://www.10000words.net/2009/05/top-7-types-of-twitter-avatars.html

Tromp, J., Bullock, A., Steed, A., Sadagic, A., Slater, M., & Frecon, E. (1998). Small group behaviour experiments in the COVEN Project. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 18(6), 53-63.

Vander Valk, F. (2008, June). Identity, power, and representation in virtual environments. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4(2). Retrieved January 30, 2009 from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol4no2/vandervalk0608.htm

Wexelblat, A. (1998). Don't make that face: A report on anthropomorphizing an interface. Retrieved May 10, 2009 from

http://www.aaai.org/Papers/Symposia/Spring/1998/SS-98-02/SS98-02-028.pdf

Wood, N. , Solomon, M., & Englis, B. (2005). Personalization of online avatars: Is the messenger as important as the message? International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 2(1/2), 143-161.

Yee, N. (2008). Our virtual bodies, ourselves? In The Daedalus Project: The Psychology of MMORPGS by Nick Yee. Retrieved May 9, 2009 from http://www.nickyee.com/daedalus/archives/001613.php?page=1

Yee,

N., Bailenson, J. & Rickertsen, K. (2007). A

meta-analysis of the impact of the inclusion and realism of human-like

faces on user experiences in interfaces. Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, April 28-May 03,

2007, San Jose, California. Retrieved June 2, 2009 from The ACM Digital

Library database.

Zajonc, R., Adelmann, P., Murphy, S. & Niendenthal, P. (1987). Convergence in the physical appearance of spouses. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 335–346.

Zajonc, R., Adelmann, P., Murphy, S. & Niendenthal, P. (1987). Convergence in the physical appearance of spouses. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 335–346.

copyright 2009

© David Taylor

david@peakwriting.com

Second Life: David Hecht

Permalink: http://www.peakwriting.com/UMUC/onlineguide/av_solution.html

david@peakwriting.com

Second Life: David Hecht

Permalink: http://www.peakwriting.com/UMUC/onlineguide/av_solution.html